The world’s most liveable cities have a lot in common — they’re safe, economically prosperous, eco-friendly, and afford a high quality of life. They are also typically world leaders on transport and urban planning — which, although often overlooked, sets them apart from other urban centres while also being key drivers of economic growth and prosperity.

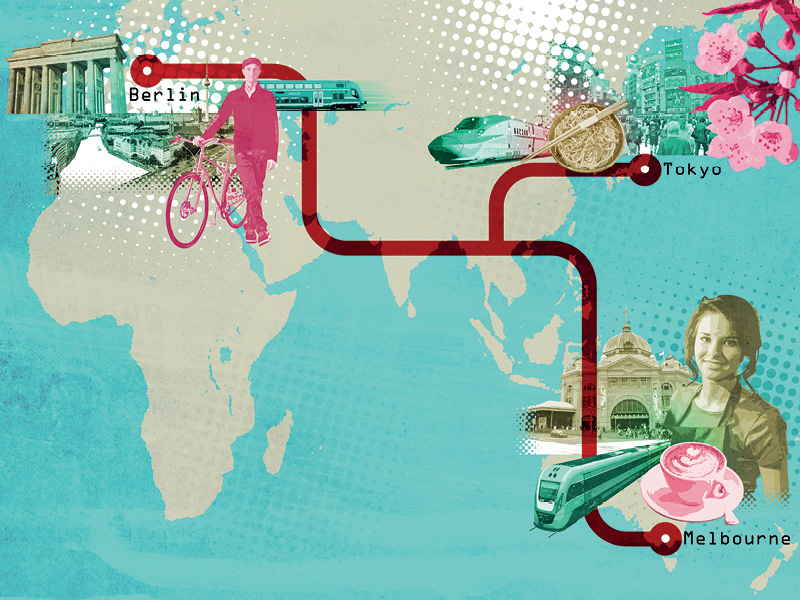

Whether it’s Tokyo’s high-speed bullet trains, Melbourne’s integrated tram network, or Berlin’s cycleways, transport, logistics and smart urban design lie at the heart of these three liveable cities.

Tokyo

Japan’s capital city is no stranger to top rankings on liveability indexes. The sprawling metropolis of more than 13 million people often features in top 10 lists, and in 2016 came highest in the quality-of-life ranking in British lifestyle magazine Monocle for the second consecutive year.

The city — whose population balloons to more than 20 million if nearby areas of Kanagawa, Chiba and Saitama are included — often scores especially high on metrics like housing, cost of living, public space, crime, and facilitating business. Many of these positives are supported by the city’s outstanding transport network, including its superb metro system and links to the nation’s bullet train line — infrastructure that’s crucial when it comes to liveability.

“Allowing different eras of a city to persevere and be expressed in the urban fabric creates a more vibrant, more liveable city.” – Aaron Davis, University of South Australia

Aaron Davis, from the University of South Australia, says the beauty of the Shinkansen high-speed rail, which sees trains travel at speeds of 210 kilometres per hour, is that it enables daily commutes to Tokyo from far-flung locations. The genius in this system, the Japanese expert says, is it allows more density and fewer highways in Tokyo’s CBD.

“Japan’s cities have largely been shaped by their role in the bullet train network across the country,” explains Aaron. “Within the cities, there’s a large focus on rail networks and public transit rather than private transit, which has helped to facilitate more density around the way they’re developing their cities.

“Generally, the focus on allowing public transit development rather than private motor vehicles means that they can have a lot less freeways and motorways within the centre of the city.”

The end result, he says, is that urban density can be lifted without residents losing quality of life, while also maintaining ease of movement. Aaron puts it succinctly: “It’s just really easy to get from point A to point B throughout Tokyo’s public transit network.”

Tokyo’s rich urban fabric is another big plus for liveability, he says. Unlike some other global cities, Tokyo hasn’t totally erased its urban heritage, with the towers of Shinjuku sitting alongside closely packed informal streets, shopping centres coexisting with street markets, and pockets of traditional houses pushing up against office skyscrapers. He argues that this rich ‘layering’ gives Tokyo a peerless vitality and visual energy.

“There’s a focus on allowing the city to develop over time so each decade and each movement in the city is allowed to make its mark. In Tokyo, where you’ve got the old juxtaposed against the new, the urban areas become really vibrant and exciting,” Aaron says. “When a city becomes one dimensional in its architecture and its urban feel, it becomes boring: it’s not visually stimulating, it’s not culturally stimulating, and it becomes a bit of a non-place. Allowing different eras of a city to persevere and be expressed in the urban fabric creates a more vibrant, more liveable city.”

Aaron explains that the city’s positive lead on heritage can be hard for other places to follow, because it’s largely a symptom of Japan’s lengthy economic slump.

While unfettered development has taken place in many growing Asian cities — Shanghai is a case in point — Japan’s slower growth rate has eased development, resulting in many older buildings dodging the wrecking ball. That’s not a bad thing, according to Aaron. “It’s about taking that time to assess what is there in the present and assessing the culture of a place before saying, ‘Let’s put a bulldozer through it all’,” he says.

Melbourne

While Japan often looms large in global indexes, it could be argued that Melbourne is today’s global benchmark for urban liveability. Previously regarded as Australia’s ‘second city’, Melbourne now often outranks Sydney when it comes to liveability, taking out the Economist Intelligence Unit’s liveability index for 6 consecutive years.

In the 2016 index, Melbourne beat contenders like Vienna and Vancouver, while major global hubs like London, New York and Paris slipped down the list due to higher crime rates, congestion and public transport woes.

Melbourne, meanwhile, received stellar marks across the board. It was praised for its stability, healthcare, culture, environment and education, and even notched up a perfect 100 for infrastructure, demonstrating the importance of the city’s roads, public transport, and international links to the lofty ranking.

It’s not hard to see why. Melbourne boasts a global benchmark tram network, the nation’s largest container and automotive port in Port Melbourne, and integrated citywide cycleways that massively boost liveability.

The city’s tram network — the largest in the world — is particularly impressive, featuring 250 kilometres of double track and 1,763 trams, while 80% of Melbourne’s tram network shares road space with other vehicles.

And it doesn’t stop there, with the city bringing more mass transit infrastructure online, including the new Melbourne Metro Rail comprising a nine-kilometre twin-rail tunnel under the CBD that adds five new stations to the network.

In addition, low population density, numerous housing options, its cosmopolitan culture, and an emphasis on green spaces have also been identified as factors contributing to Melbourne’s enviable status as the world’s most liveable city.

The University of Melbourne’s John Stone acknowledges his hometown’s status as a world leader, but says The Economist ranking does have limitations. “Those rankings focus on what’s happening in the central city and The Economist is saying, ‘If you’re an expat living in Carlton and working in the city, you’d find things pretty good.’ That’s really what they’re measuring,” he explains.

The urban-planning expert says truly assessing how liveable Melbourne is, for those who actually live there, means taking off some of the city’s gloss. Quality of life for those in the middle of town may be world class, but John says many of the city’s 4 million residents who live outside the CBD are being let down by transport and land-use planning in the Victorian capital.

“There are real problems for the majority of Melburnians who live in the suburbs,” he says. “Basically we have spent the last 40 or 50 years making it difficult for them to choose anything other than a car for almost all their trips.”

John says in the past a small population meant it was possible for commuters in Melbourne “to experience the freedom that the car was supposed to deliver”, but argues that time is long gone, pointing to the fact that the city’s weekend traffic congestion now rivals weekday peaks.

A key to improving the situation, he believes, is to boost amenities near public transport hubs — a strategy already utilised by many forward-looking global cities. “It’s a land-use question,” John says. “Around our public transport nodes, we need to have the jobs, the schools, the healthcare so that people can actually travel by public transport, by foot, or by bicycle.

“Right across the board, we need to set targets for reducing our dependence on cars,” he explains. “If we had a seriously planned target and followed it through, that would put us on a really good track.”

Berlin

One of 10 cities to suffer a fall in The Economist’s liveability ranking last year, the German metropolis is nonetheless a common fixture on quality-of-life polls, coming in second in Monocle’s 2016 index.

Increased fear of terrorism after the Paris and Brussels attacks was the main reason the city slipped down the index. Nevertheless, Berlin continues to perform well on climate, architecture, crime, the environment and business.

Another big reason the city of 3.5 million people is so liveable, experts say, is its integrated and well-functioning transit system.

First off, there’s Berlin’s multimodal public transport strategy, which means the rate of car ownership is low in the city, with just 324 cars per 1,000 inhabitants. That flows through to less congestion, fewer highways, and more space for housing and open space.

Chris Pettit, from the University of New South Wales, says Berlin could be considered a good example of a ‘30-minute city’, which could be a key reason it’s often identified as one of the world’s most liveable places.

“As humans, we typically try to optimise our commuting so that it’s no more than an hour each day. If you dissect that each way, you’d crudely have half an hour for one trip in one direction and half an hour in the other direction,” the urban science professor says. “Really, it’s about trying to minimise travel time.”

Berlin also demonstrates how an integrated public transport network — there are ferries, buses, local and regional trains — can work seamlessly and efficiently to move large groups of people from one place to another, without any hassles.

This is no accident. Policymakers in Berlin appreciate the interaction between transport and liveability, so not only encourage the use of mass transit but also dissuade people from using private vehicles. Rules include making parking permits only available to locals, drastically limiting parking space in the city centre, and removing free parking entirely from the CBD.

As Berlin demonstrates, ensuring a city has top-level public transport is a massive boost to liveability. “That’s the take-home message,” says Chris. “The cities that are performing

well on liveability have excellent public transport.”

Excellence includes trains, or indeed any form of mass transit, running on time. “You don’t want to have people waiting a few minutes for a connection. So sometimes you can have a large network, a big footprint of the infrastructure, and then there’s the frequency and connectivity to look at,” he says.

Transport aside, Berlin has also been praised for its unique approach to transformative urban planning and logistics, especially when it comes to renewing abandoned buildings. All across the city, there are examples of derelict structures given new life, whether it is as offices for start-ups, artist studios, or even temporary housing for asylum-seekers.

One high-profile success story is the Haus der Statistik in the centre of Berlin. A former government building, the sprawling 130,000-square-metre property now contains artist residences and refugee accommodation, and has been hailed as preventing the capital’s drift into ‘normalcy’.

“The cities that are performing well on liveability have excellent public transport.” – Chris Pettit, University of New South Wales

Chris says cities that score high on liveability usually also make themselves super amenable to walking and cycling. This is certainly true of Berlin. There are an estimated 500,000 daily bike commutes across the city, accounting for about 18% of total traffic, and there are a whopping 710 bicycles per 1,000 residents. The positives aren’t hard to see, with more bikes meaning healthier, less-stressed residents.

“As we’re implementing the compact city — denser and taller — it’s important to make sure we’ve got enough space for walking and for cycling,” Chris adds. “Dedicated cycle paths that separate pedestrian cycle infrastructure and support the movement of people through active transport are key. It’s a big issue because kids are not walking and cycling to school nearly as much as they used to a decade ago.”

Whether it’s making sure kids get more exercise or improving mass transit, Chris says improving cities in today’s world will ultimately mean “making them smarter.” “We can get smartphone data, and map — on a fine scale — to determine how people are navigating through the city,” he says.

“Having that data-driven approach to better city planning means we can use it to understand how people are moving through the cities, where the bottlenecks are, and how to improve the infrastructure into the future.”