In May, the European Central Bank announced it would stop producing the €500 note toward the end of 2018. It was the first assault on large-denomination bills in what many see as a global shuffle toward the “cashless society” that’s been discussed since the first credit cards first became a reality in the 1960s.

The decision by the ECB was based on “concerns that this banknote could facilitate illicit activities”, which seems to be a concern shared by economists all over the world. It is generally expected that the US will similarly send the $100 greenback packing, and Australia would follow suit. (Interestingly, Switzerland, the nation famous for its cloak-and-dagger bank accounts, has flatly refused to consider phasing out its 1000-franc note, the world’s largest denomination bill in the world.)

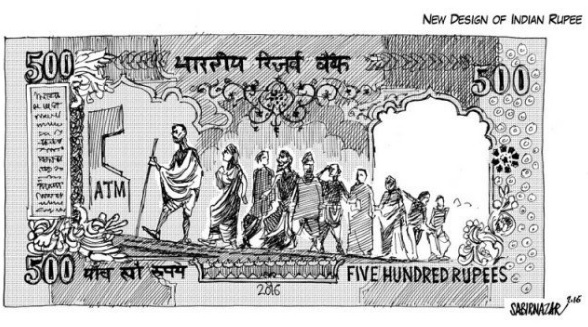

But the most striking step of all was taken by Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, who, last month, in what is regarded as the most extraordinary change in currency policy in history, “demonetized” the existing 500 and 1000 rupee notes, virtually overnight. In one sweep, millions of low-to-middle income earners who’d never held bank accounts in their lives, and who’d been hording the notes in private stashes, faced losing what they would regard as “fortunes”.

Like the USB, the Indian government claimed the move was designed to slaughter the criminal black market, but the fallout has been civic chaos and the decimation of a relatively innocent underclass. Reports from India tell of stampedes and mile-long queues at banks and ATMs as customers try to replace their ready cash reserves, planeloads of cash flying in and out of the country as desperados try to launder funds, and priests advertising charity donations, which are exempt from government scrutiny, as means by which parishioners can safely exchange dirty money for a modest fee.

Furthermore, as was reported by Slate, “only about one-third of Indians currently have internet access. And most of them can get it only through mobile devices because the country’s broadband supply is so limited outside urban areas. There simply aren’t enough wires in the ground. Mobile connectivity is patchy, even in cities. This reflects wider infrastructural problems that have never been solved: Hundreds of millions of people are also without a stable electricity supply or efficient sanitation. In India, grand ideas are plentiful; implementing them is rarely straightforward. And a country that is largely offline is perhaps not ready to go cashless.”

Any doubts Narendra Mori might have had about the popularity of this decision must surely have been put to rest when footage of a crowd of thousands burning him in effigy was broadcast over the media. Which is not surprising considering that an estimated 86% of the cash in Indian society was held in the now-cancelled denominations, and that the Government’s owns statistics reveal that only 1 percent of the population pays tax — that’s 99 percent of the population that Mori has managed to instantly enrage.

The problem here is that, while it’s true that the rupee is the third most counterfeited currency after the euro and the US dollar, and despite the “demonetization” being supported by some economists and political thinkers, it does seem to be incredibly naïve (and economists and political scientists, who deal in models, do have a tendency to be a bit green when it comes to the real world).

The notion that billion-dollar crime cartels only deal in cash is absurd. Any criminal empire with a brain in the hierarchy would ensure profits were converted into foreign exchange, gold, bitcoin or a similar transferable, if not plunged into real estate or luxury items immediately. It is also unthinkable that criminal empires in the 21st century have not orchestrated ways to circumvent technological detection — that the Pablo Escobars of our time do not invest in hi-tech help to disguise their digital transactions.

In any case, Narendra Mori followed up the “demonetization” by instantly releasing new 500 and 2000 rupee notes, which will undoubtedly replace the old black-market currency as the criminal notes of choice. In time, the entire anarchic exercise will have served no purpose but to have punished petty criminals, stung a few low-level toll dodgers and buried taxation agents in career workloads the size of the Himalayas — and the impact it has on the business community will be to a degree only the future will tell.

One can only hope that the west is paying attention as we are inevitably propelled toward a world without cash.