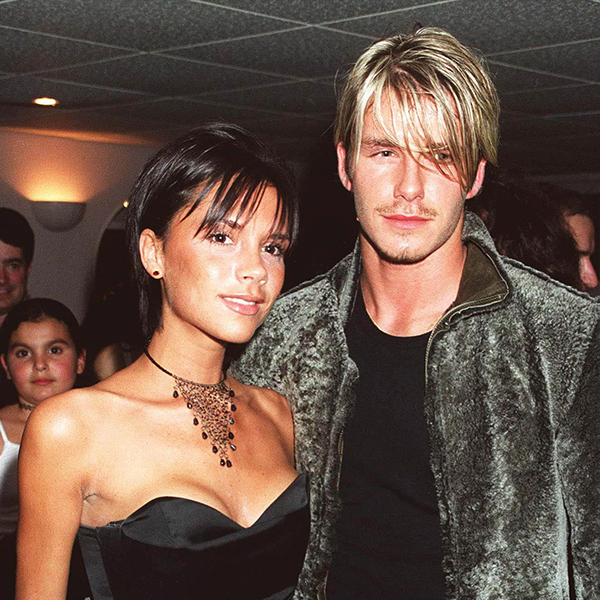

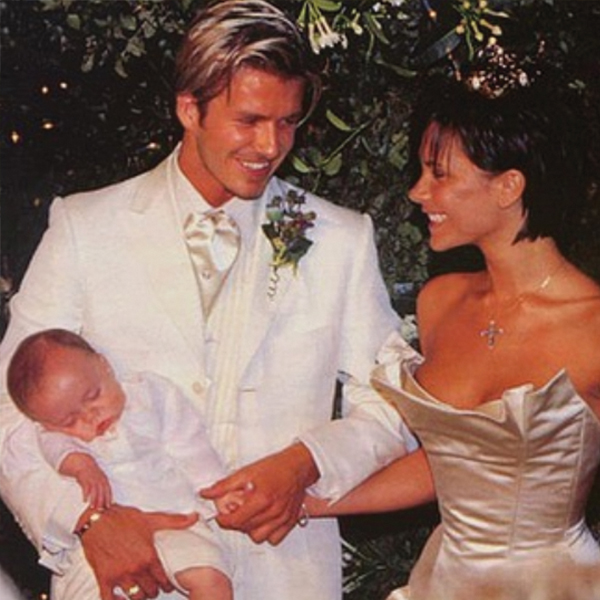

The existence of The Beckhams proves different things to different people, depending on how deep their chasms of cynicism run. One harsh truism is that you don’t need talent or intelligence to succeed, which is a perhaps cruel summary of Victoria ‘Posh Spice’ Beckham’s seemingly inexplicable rise to fame.

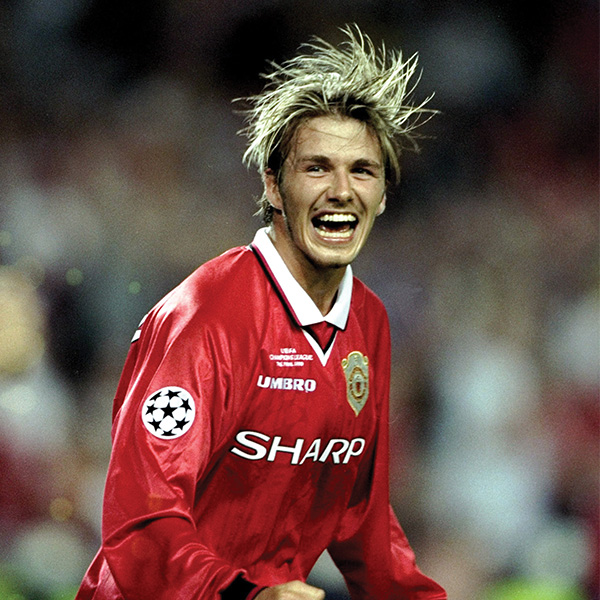

Despite a singing voice with all the sweet, velvety tones of a cat gargling glass and all the natural rhythm of a forklift, she became a pop star, and then an icon. Then there is her husband, David, a man who proves, for some, that God has a wicked sense of humour.

He made Beckham an adonis of singular beauty, and gifted him again with footballing talent that would make him England’s hero, but then cursed him with a voice that made Porky Pig sound manly. Many may have laughed at the celebrity super couple (particularly if they’ve seen their singular turn on Parkinson), but it’s the Beckhams who have laughed longest, and last.

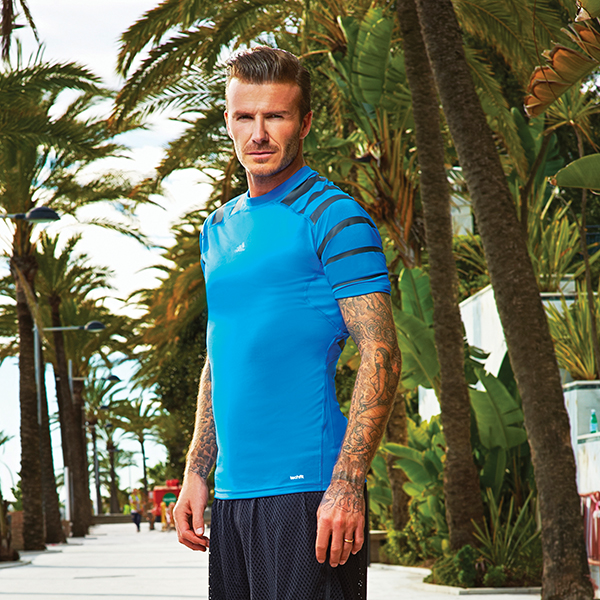

Somehow, despite the fact David hasn’t laced up a football boot since 2013 (and was at his playing peak more than 15 years ago), and that the Spice Girls disbanded in 2000, the uber-couple have managed to maintain a firm grip on the spotlight, enjoying superstar status the world over, and earning staggering amounts in the process.

The Beckham empire

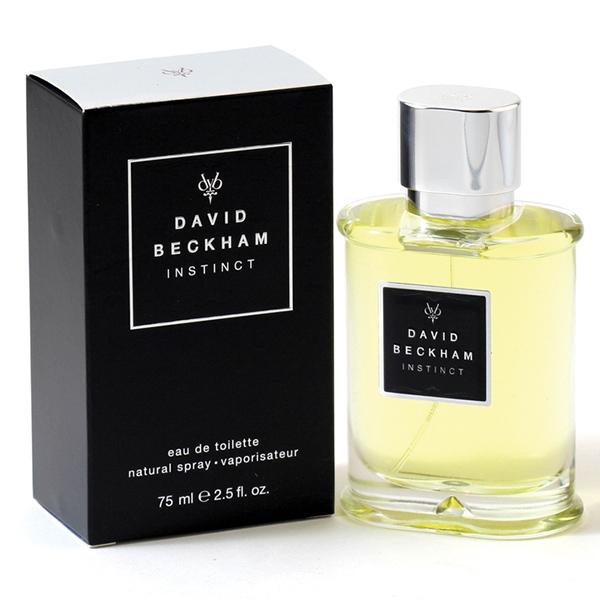

While it’s difficult to grasp the full size and scope of the Beckham empire, there are plenty of hints in the numbers. In 2015, Beckham Brand Holdings – a company the couple set up in 2013 to manage the licensing of David’s name and image, along with Victoria’s fashion line – pulled in a staggering A$77.9 million. Even the couple’s tax bill is impressive, with the company reportedly paying A$30,000 on its earnings. Every single day.

[owl_carousel class=”hide-dots owl-small”]

[/owl_carousel]

Their octopus-tentacled business has grown to such gargantuan proportions it’s hard to even see the edges now, with David’s likeness attached to everything from whiskey to watches and cologne, while Victoria has been responsible for designing clothes, sunglasses and even Range Rovers.

So what’s the secret to their enduring success in an era in which brands come and go at the speed of light, and in a marketplace with an attention span that shifts onto the next big thing even faster? Or, more importantly, how can you brand it like Beckham?

Mastering the Madonna Curve

Brand experts refer to it as a Madonna Curve, but what they’re really referring to is the (actually talented) pop star’s uncanny ability to stay ahead of it.

In short, any brand that invests heavily in marketing and visibility should – unless something is drastically wrong – see a natural spike in consumer interest, but it will also eventually reach a peak, the top of the curve, after which interest will flatten out or, more likely, start to drop as people get bored with it or its products.

The trick, then, is to shake up what you’re doing – be it your image, your offering or your marketing – before you hit the peak, resetting that curve before your brand enters the red zone.

Mastering that skill can be the difference between creating a brand that stands the test of time and one that falters and disappears. Or to put it another way, a Kim Kardashian rather than a Paris Hilton.

Vince Frost heads up the Frost*collective, a multichannel agency that helps people and businesses define their brands, and maintain them. He says the Beckhams have mastered the art like few before them, ensuring they’re never out of fashion. “It’s the Madonna Curve,” he says.

“There’s this growth, like a bell curve, and most brands start on the left-hand side. Then they position themselves, go to market, and they grow quite rapidly. But when they get to the top of the popularity peak, they then dip back to the right side of the curve.

“And that’s often when a brand has left it too late, and they need to reinvent themselves or reposition themselves so they can compete with new competitors and get further exposure.

“Madonna constantly and continuously reinvents herself before she gets to the top of the curve. She might come out with a new album, a new look. She never dips into the red, which is so much harder to pull out of when you do.”

It’s a trick the Beckhams have so thoroughly mastered they could be teaching a class in it. Entire rainforests could be replenished with the pages that have been dedicated to David’s haircuts alone, although the less said about the cornrows, the better.

Add to that the new clothing lines, products, movie roles – even the intense focus on their growing family; the next generation of their business – all of it feeds back into the Beckham brand, capturing the spotlight before it can be trained elsewhere.

“The Beckhams were at the very top of their careers individually, and then coming together they’ve become this sort of super-couple, and they’ve been very much focused on building those personal brands ever since,” Frost says.

“And they are very good at it, evolving and repositioning themselves so they don’t go in and out of fashion. People have come and gone since then, but they’ve managed to maintain their place as icons.

“The ones with longevity are the ones who evolve and stay relevant. There are always going to be one-hit wonders who don’t evolve or don’t grow. But the Beckhams have stayed visible, and so they remain one of the world’s biggest brands.”

Too big to fail?

Remember Blockbuster? What about Kodak? Polaroid? Nokia? All brands that held the dominant position in their respective fields, and all now slowly rotting on the scrap heap of history.

Kodak, for example, held more than two-thirds market share of the pre-digital film business, back in 1996, and was valued at US$31 billion.

And yet, despite itself inventing the first digital camera, back in 1975, it managed to miss the market shift and was dead in the water by 2004, eventually filing for bankruptcy in 2011.

The Beckhams have stayed visible, and so they remain one of the world’s biggest brands.

It’s easy to point the finger at changing technology as the cause of death but, according to the University of New South Wales’ Professor of Marketing, Mark Uncles, the blame lies elsewhere.

Netflix, for example, began life as a DVD-rental site, while IBM, savaged by the rise of the PC, recorded losses of US$5 billion in 1992, before reinventing itself as a provider of IT and cloud-computing services. Both are still going strong.

“Brands themselves, of course, are just names. So there’s nothing intrinsic in them that would suggest that one should last forever while another only has a short lifespan,” Uncles says. “It’s the people behind the brand who make the difference.”

Fail to prepare, prepare to fail

“What is crucial is the way that the brand is actively managed,” says Uncles. “Success or failure is not an inherent attribute of the brand, it’s what the managers do with that brand.

“The challenge is that not only do you have products changing over time, you have consumers changing too, and so their preferences and the things that resonate with them also evolve. Our tastes, preferences, values – they all grow and change, and so a brand has to as well.

“Some organisations have been very adept at evolving – so you’ve gone from a brand that started off with one category, and the management team might have been able to see other possibilities in other categories or other geographic locations.

And you’ve got some brands that haven’t.” A prime example, Uncles says, is the now run-and-won battle between Nike and Reebok. Flashback to the late 80s when Reebok was the dominant force in the American sneaker market, ahead of arch-rival Nike. And then, it wasn’t.

A brand is a living entity – it’s not something that

you just issue guidelines for.

In 2016, Nike’s revenue was US$32.4 billion. Meanwhile, a floundering Reebok was sold to Adidas in 2005. So what the hell happened? The problem, Uncles says, was brand maintenance. Reebok was allowed to stagnate, while Nike continued to invest in stores, products and sponsorship. Had the roles been reversed, he says, then so would have the outcome.

“Nike became very available, both through physical stores and online, and it’s also very public. It invested a huge amount in advertising and sponsorship and star ambassadors and so forth,” Uncles says.

“It’s not just the name or the product, it’s the spend they’ve put behind it.

“Clearly Reebok wasn’t able to support that, and entered a downward spiral where suddenly it wasn’t making as much money, so wasn’t as available, and couldn’t spend as much on advertising and sponsorship.

“One of the biggest mistakes you can make is failing to invest in

a brand, because you think you don’t need to. If a brand has been around a long time and historically people like it, people buy it. And so you neglect it, thinking you don’t need to invest too much in it.

“But that’s not the case. More relevant brands come along to replace it, and your brand dies. I don’t think there’s ever a meeting where a CEO says they’re going to kill a brand. What they’ve done is kill it through neglect.

“There is the thought, though, that death is inevitable. If there is a levelling off or a decline in consumer interest, and management can’t think of anything highly creative to do with the brand, then it should be allowed to die. You don’t want to be responsible for a premature death, though.”

Believing that a brand is too big to fail is a shortcut to disaster, agrees Frost, who says the amount of work required to stay relevant in a fast-moving environment is greater than ever before. Again, think Kodak or Nokia.

“Brands need upkeep. That’s what happens with those brands that are massive global entities. They just don’t evolve, they are nurtured to become strong, powerful and successful.

If they aren’t tended to or don’t evolve fast enough, they simply become obsolete,” he says. “It used to be that when we were working on a large-scale brand for a client, they would enter a seven- or eight-year cycle, after which time they’d come back and say we need to refresh the brand. If they took that approach today, they’d be out of business in three years.

“You need to be agile, and focused on what the market is doing, what your competitors are doing and what’s new. You need to move with the times – and the times are moving faster than ever before.”

The era of the personal brand

If you’re thinking all of this is only relevant to celebrity ambassadors or multinationals, it’s time to think again. We’re all creating and curating our personal brands, only instead of shopping them to customers or shareholders, we’re pitching to potential employers, colleagues, even in-laws.

“Everyone now has a personal brand, thanks to social media, which is something we’ve never had before,” Frost says. “You can Google anybody today and the information is out there. Whether it’s on Facebook or LinkedIn or just Google itself. You can’t hide from that exposure, which has its benefits and its detriments.”

Any major recruiter applies the Google test as the first check of a potential candidate, and if yours reveals ranting Facebook tirades or some long-forgotten (but no less offensive) Tweet, yours will be the first resume into the bin.

“A brand is a living entity – it’s not something you just issue guidelines for. It’s something that needs to be agile, changing, constantly looking at the feedback. It’s a world of phenomenal technology, and we can access anything at any time, and it’s important to utilise that to maximise your potential.”