At the family owned German automation business ifm electronic, succession came with a series of hard rules, in particular a five-year probationary period.

“We were not invited right after our studies into the company,” Co-Chair and Managing Director Michael Marhofer tells The CEO Magazine. “We had to find our way in other businesses to a certain point, and then we had to take another five years within ifm before we took over any responsibility.”

The agreement was that they could be tested by the older generation several times during that period. “During that time, if they said we were not the right guys, then we would have left. Likewise, if we thought we weren’t a fit, it was OK for us to step away.”

The ‘we’ he is referring to is himself and Martin Buck, sons of ifm founders Robert Buck and Gerd Marhofer. As it happened, their two sons were born for the role.

The passing of the baton to the second generation took place in 2001, 32 years after their fathers first started selling small sensors to the German market. The founding pair – Buck, an electrical engineer, and Marhofer, a salesman – grew their business into a leading name in the automation industry with locations around the world.

“It was a good agreement because it gave freedom to both parties without destroying the company,” Marhofer reflects. “We both knew we had a certain period of time to really make a decision.”

And once that decision was made, both fathers immediately stepped away. “There was no longer an office or an official position, even on the supervisory board.”

We don’t get projects without the software, because at the end of the day the customer wants a one-stop solution.

New directions

As Co-Chairs and Managing Directors, this second-generation partnership has proven as successful as its first. In the past two decades, under their direction, ifm has become “an international company born in Germany,” as Marhofer describes it.

The business now develops, manufactures and markets sensors, controllers, software and systems across an array of industrial automation usages including in the automotive, renewable energy, conveyor technologies, agriculture, food and logistics sectors. It has a presence in 80 countries – 50 of them as subsidiaries – and employs more than 8,100 people.

“The company has a lot of personality,” he says. “A lot of people have been with us 10, 20, 30, even 40 years, and it’s these people and the stability of their jobs that are the main drivers for me in the role.”

So much so that positioning the business in a new direction not long after taking the reins is what Marhofer names as the biggest challenge he’s faced, not the COVID-19 pandemic nor the 2008 financial crisis, he says.

“In 2005 we saw that digitalization was coming and that we needed to completely change our way of thinking,” he says.

The actual practicalities were simple – the decision to integrate digital communications into its sensors was easily made as the company added software to its primarily hardware product portfolio.

The ongoing success of ifm made the next step harder. “Our business model was still strong in hardware, so convincing our people that we had to invest massively in software was difficult,” he admits.

Even today, the majority of turnover can still be attributed to hardware.

We really try to build up a company that is good for people, for the environment and for society.

“But it was absolutely the right decision. We don’t get projects without the software, because at the end of the day the customer wants a one-stop solution.”

Thanks to these software capabilities, ifm has stayed at the forefront of technology to offer customers value-added solutions such as predictive maintenance tools. Acquisitions drive innovation as well.

“We are going to Israel, to Scandinavia, to California, all over the world looking for new startup technologies,” he says, adding that it’s a strategy that also opens up new markets and new business for the company.

Purpose with profit

With a target of achieving climate neutrality in its operating business by 2030, both generations of ifm leaders were practicing purpose with profit long before it was a business buzzword. “We’re not a non-profit organization, but we really try to build up a company that is good for people, for the environment and for society,” Marhofer says.

Since 1990, the promotion of ecologically conscious decisions and conduct has been at the center of its corporate philosophy. “We started by measuring our energy and water usage and looking for ways to save both before anyone else was discussing it,” he says.

In the last 15 years, overall energy consumption has been drastically reduced, so much so that three years ago, 100 percent renewable energy across operations was achieved.

Last year the company took it a step further with the announcement that its new factory in Romania would be certified green. Photovoltaic modules and heat pumps are two of the technologies that will allow the plant to be self-sufficient in energy terms.

Alongside this is a commitment to manufacturing as much as possible with components made in the same region as the factory to limit unnecessary shipping during the production process.

At the very core of ifm, Mahofer emphasizes, are the sensors themselves that promote sustainable practices. The majority are designed to stabilize production processes and, in doing so, limit rejects and preserve resources.

Delivering products that are really able to withstand solid usage for decades is a part of sustainability, too.

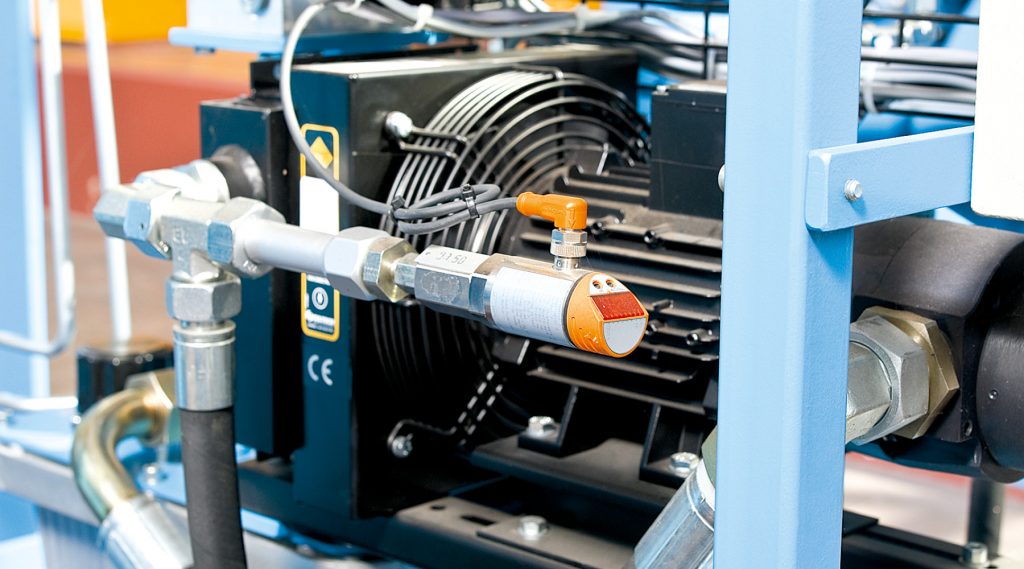

An example is the Thermal SD Compressed Air Meter, which monitors volumetric flow. The device’s ability to detect leaks in compressed air supply systems can result in significant energy savings.

Like the business itself, every item in ifm’s portfolio is built to last. “Delivering products that are really able to withstand solid usage for decades is a part of sustainability, too,” Marhofer explains.

ifm Spotted

Atop the snow-covered Piz Corvatsch near St. Moritz in Switzerland, 3,303 meters above sea level, the highest distillery in the world, Orma Distillery relies on ifm SM Magnetic inductive flow sensors in its production of a range of whiskeys – including a special edition aged in wine barrels stored in a mountain cave.

And while it might not make ifm the cheapest in the market, those customers and potential customers who take the time to calculate the lifetime cost realize that there’s no better value to be found.