When Lucknow Metro resumed operations in June after a month of complete lockdown, the health and safety measures it put in place were extensive. Contactless travel, sanitisation, social distancing, hygiene and cleanliness were among the policies implemented to set commuters’ minds at ease, explains Uttar Pradesh Metro Rail Corporation (UPMRC) Managing Director Kumar Keshav.

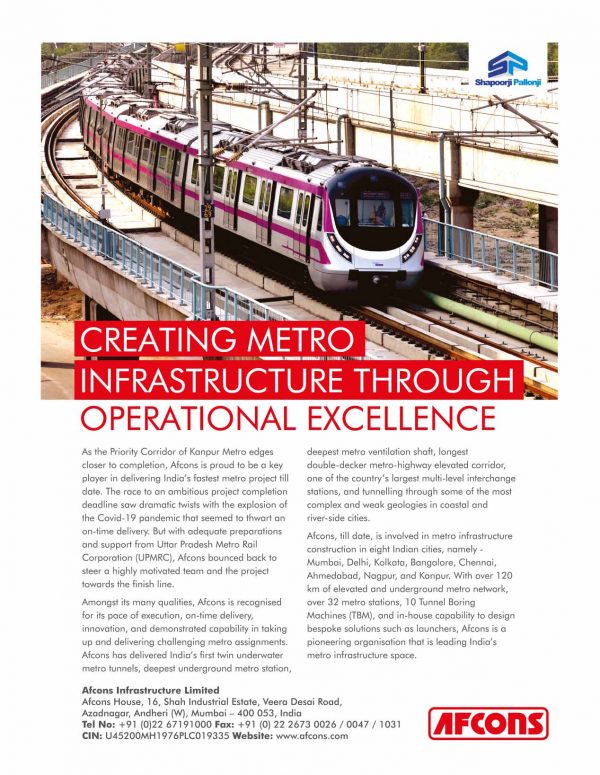

The past few years have been quite challenging for Kumar, to say the least. When The CEO Magazine last spoke to him in 2018, Lucknow Metro was operational on the Priority Corridor. The priority stretch of Lucknow Metro took about three years to be operational, which is an achievement in itself and, by the beginning of 2019, the Lucknow Metro was operational on the entire 23 kilometre North-South corridor.

Despite the many challenges and technical intricacies involved, the project had taken only four and a half years to complete. This makes Lucknow Metro one of the fastest executed metro projects in the country, with operations able to start before deadline. Initially, the organisation was known as Lucknow Metro Rail Corporation.

However, with the expansion of projects in Kanpur and Agra cities, the company’s scope grew and to reflect this, it became the Uttar Pradesh Metro Rail Corporation in 2019. “The good thing about the Lucknow Metro was that both the government and the people had confidence in it. They believed that a project of this magnitude could be completed on time and within budget,” Kumar says.

Stakeholders felt such confidence that plans were made for both projects to include two corridors. The new Kanpur Metro will be 33 kilometres, with 11 underground stations and the remaining stations elevated. Agra will have 30 kilometres of track and seven underground stations, with the remainder above ground.

According to Kumar, the decision to go underground was largely driven by a desire to serve congested areas and to preserve both cities. “We want to retain our archaeological heritage,” he stresses. Along with the Kanpur and the Agra metro projects, there are plans for an additional East–West Corridor for Lucknow Metro.

“It has to obtain clearance from the state government. Once it has that clearance, it will go to centre for final approval. We are hopeful to get all due clearances and start the work very soon.” Once this happens, there are proposals for five more corridors to further boost the city’s connectivity. The company expects between 500,000 and 700,000 people to travel by the metro every day in the next 10 years.

An unexpected disruption

These plans, as well as the metro’s entire operations, were thrown into disarray as the pandemic prompted a lockdown to help get the spiralling virus under control. For more than 60 days, it was closed to commuters.

Determined to maintain seamless operations once COVID restrictions were lifted, Kumar insisted on running an empty train along the corridor morning and night to keep the system running smoothly. He initially operated these services himself, until staff gained the confidence to take over.

“We partnered with the local police, who helped by providing a bus that would bring staff to the metro station,” he reveals. “I had to ensure the utmost safety and security of the metro trains by carrying out regular inspections and motivated my team to be prepared for the challenges arising due to the pandemic.”

Although the company was incurring losses during this period, Kumar’s foresight proved that when Lucknow Metro was permitted to start operating again, it could be quick off the mark. “On 7 September, we were fully ready to start services immediately because we did not stop operations for a single day,” Kumar says.

However, once the trains started welcoming commuters after the lockdown came to an end, it was a different ball game. Prior to the closure, it had been transporting around 72,000 people per day. When it resumed operations, that number plummeted to just 6,000. “My team was very discouraged,” Kumar admits.

We developed a business continuity plan to ensure the safety and security of my own people and the safety and security of our commuters.

“Nonetheless, I started from day one with 100% operations, thinking, ‘Even though the trains are empty, let people gain confidence – we are here for them.’” By May, when the colleges reopened, that number had risen to 42,000, with Kumar confident it would keep climbing.

Becoming COVID-safe

To start winning back the confidence of commuters, it was essential for UPMRC to ensure everyone felt safe while travelling on its trains, so it overhauled its operations to make them COVID-safe.

“We developed a business continuity plan to ensure the safety and security of my own people and the safety and security of our commuters,” Kumar recalls. “Then, we shared it with everyone via WhatsApp and email. We sent it to everyone; schools, colleges, and advertised it at the stations and explained to them how we would operate our trains for the passengers’ safety.”

The entire staff wore gloves and masks, also making it mandatory for all commuters to wear a mask. “Everyone was bringing their own, but in case they were not, we were giving them masks too,” Kumar says.

Although the company still offered tokens, sterilising them each night before putting them back in the system for re-use, it actively encouraged users to adopt its contactless GoSmart Card option.

“This is the perfect time to start using one,” Kumar explains. “People have understood the benefits and, now, many people have made the switch.” All trains were sanitised extensively during the night with sodium hypochlorite solution. Drawing inspiration from the New York Metro, the trains then began to be sanitised with ultraviolet rays for added safety.

Using equipment certified by the Defence Research and Development Organisation, the company is able to remotely sanitise an entire train carriage in just seven minutes. However, to ensure the train stays bacteria-free, a 15-minute process is used instead.

“Lucknow Metro is the first metro in India to adopt this UV technology,” Kumar says, revealing it is considered more economical than manual cleaning and sanitisation measures. High-touch areas are continuously cleaned throughout the day, he adds. Other measures include using alternate seats, signage, social distancing and limiting the number of people in lifts. “Everybody has supported us with these initiatives,” he says.

Getting the Lucknow Metro back up and running was just one side of the equation. The lockdown meant all work on both the Agra and the Kanpur Metro projects had to come to a halt. Work on the Kanpur Metro had originally started in November 2019 with almost 4.5 kilometres having already been completed.

“Kanpur is the industrial capital of Uttar Pradesh and it’s an old city, very densely populated with a majority of working class people who travel to the centre,” Kumar explains, adding that the progress has been swift. Fortunately, the new metro line only passes by two monuments of archaeological significance, so it obtained approval quickly.

“We are hopeful to begin our trial runs by the end of this year. That means that it will prove to be the fastest metro project executed by UPMRC.” However, the Agra Metro is a different story. Although Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath originally announced both projects in December 2017, UPMRC then had to approach the Supreme Court to obtain permission to enter the Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ) – a defined area of 10,400 square kilometres around the iconic Taj Mahal to protect the monument from pollution.

“There are a lot of environmental issues in Agra because of the TTZ. Any type of construction is banned near the Taj Mahal,” Kumar points out. “The Supreme Court directed us to complete an environmental impact study.”

The study was undertaken by the Central Empowered Committee and, in addition, UPMRC commissioned a detailed heritage impact assessment by a reputable firm. “We prepared a very elaborate report. When we went to the Supreme Court, we were fully ready with all this supporting documentation, which helped our case,” he says.

Despite all of these issues, the project received a green light from the Supreme Court with Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurating the first phase of the Agra Metro Rail Project virtually in December. With both projects finally progressing, the pandemic lockdown represented a huge curve ball.

“On the 23 March 2020, there was a complete suspension of operations and we were confined to our homes,” Kumar remembers.

Taking care of its people

Due to the new restrictions, around 2,000 workers who had been working on the projects were restricted to the labour villages that had been set up to accommodate them. Kumar proudly insists that all was “very well taken care of” during this period.

“We ensured they had adequate medical supplies and provided proper food for them because nobody was supposed to go out,” he confirms. “There were regular checks and monitoring by the doctors. We put in place a lot of precautions and, fortunately, there were no cases.”

Finally, UPMRC received permission to resume work in May, but then it faced another difficulty. After two months, the workers wanted to go home and see their families. “They were very happy with the care we had provided, but all of them were worried about their families,” Kumar says.

“So, I agreed that they could go, but they promised they would come back. And I’m happy to say they went home and, after one month, they all started to return.” Although he admits this was a challenge, Kumar understands that the problem which the workers were facing was “very genuine”.

Other younger members of his team had also returned home to their families during the lockdown period – something Kumar was again more than happy to accommodate. He stresses he could not have negotiated the challenges of the past year without the help of his team and his workers, who stayed calm and collected throughout this tumultuous period.

As UPMRC once again gathers speed on its various projects, Kumar has turned his attention to the future and how to secure the organisation’s position as an environmentally-friendly operator. For example, it has set up an automatic vehicle wheel wash machine at the Bamaurali Katara casting yard for the Agra Metro to remove the dust, mud and dirt debris from the wheels of its vehicles before they get on the road.

It is also using water sprinklers and anti-smog guns at various construction sites. These help dust particles settle down to ground level to minimise pollution. This is just another example of how Kumar finds solutions to the issues at hand.

“We have overcome these very peculiar challenges by doing our best to solve them,” he reflects. One thing’s for sure: after the disruptions of the past year, both he and his team at UPMRC are now determined to keep things firmly back on track.

Proudly supported by: