This particular column, readers, is designed to cover my backside.

Generally speaking, I’m an optimist. At the end of last year, I wrote a heartwarming article full of things to be grateful for, including the state of Australia’s economy, which is in good shape and getting better.

But Australia hasn’t had a recession for more than a quarter-century. Even though the world economy is still recovering from the aftershocks of the global financial crisis, and even though we came through the unwinding of our resources boom, we’re kind of overdue for some bad news.

So just in case everything goes pear-shaped in the next couple of years, here’s the article I’m going to point to as proof that I knew bad times could be just around the corner.

The candidates in the economic fall

There’s no shortage of candidates to play The Cause of the Next Collapse.

The Australia Housing Bubble could finally burst, with first apartments and then houses dropping in price and investors realising they’d never get their money back.

The Chinese banking system could cave in, causing an unprecedented recession in the world’s second-largest economy.

Or continued income stagnation in Western economies could cause lower-wage and no-wage workers to do something crazier than just helping to elect Donald Trump.

But honestly, if the world and Australian economies are going to fall back into slow growth or recession again, the most likely source is rising interest rates.

The financial memory problem

The problem is well put by Macquarie Group chief executive Nicholas Moore, a smart and thoughtful three-decade veteran of the financial world. According to the Financial Review, he noted in February: “For most of my working life interest rates have done nothing but go down.”

To be more precise, they’ve been mostly going down since 23 January 1990, when the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) signalled a drop in the cash rate from – wait for it – 18%. By mid 1993 they were under five per cent.

A couple of times since then, rates have bounced up from under five per cent to more than seven per cent.

But if you are under 40, there’s a good chance you can’t remember a sharp and sudden rate hike.

If you’re under 20, there’s a decent chance you don’t remember any official rate rises at all; the last one came in 2010.

“Most people don’t remember a time when…” is of course the classic recipe for an ugly financial surprise. (Recall that time in the US in the mid 2000s when most people couldn’t remember home prices ever falling?) Moore noted that at Macquarie “we think about it [rates going up] a lot. We’ve thought about it for 30 years.” Other people and companies, however, probably think less about rates going up.

Yet at some stage soon they will start going up, simply because in recent months the world economy looks to be growing more strongly that at any time since 2011.

How could rising rates trigger a collapse? By pushing startled investors to the point where they have to sell in a falling market and fail to pay their debts, triggering a cascade of bankruptcies and belt-tightening throughout the economy and creating trouble for lenders.

Why economic disaster is unlikely

This thought is clearly in the RBA’s mind too. It’s paid to avoid these sorts of scenarios and ensure “financial stability”, where lenders keep lending.

The RBA sets out all its thinking in its half-yearly Financial Stability Review. The most recent review shows the RBA’s typical worries about commercial property, the most common cause of Australian bank problems. It also shows some of their thinking about “Large Falls in Household Income” and how they would affect mortgage repayments.

But the RBA also points out that Australia has been increasing the capital banks have to hold to protect against lending problems. That’s part of the overhang from the GFC.

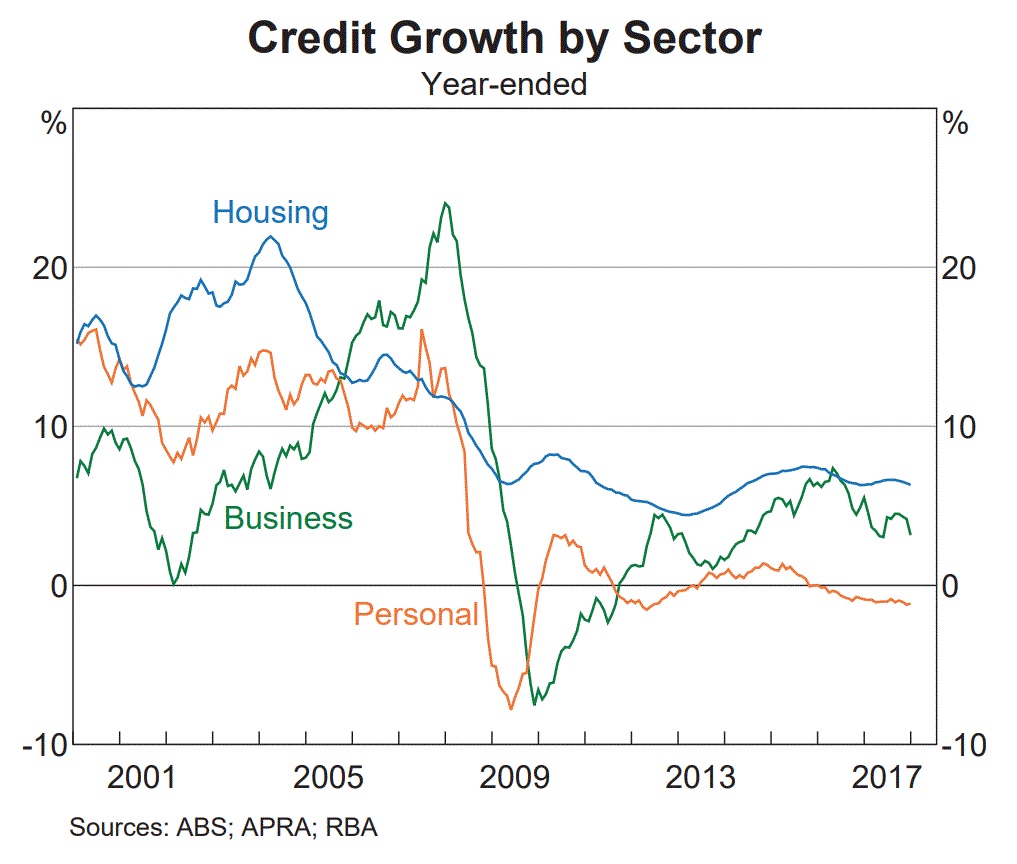

And indeed, most of the economy still looks more like it’s dealing with the last overhang from the crisis. As the RBA credit graph below indicates, right now we’re living in a far more sober economy than we were in before 2009.

And that sober mood is the best indicator that we’re unlikely to run into serious trouble soon. Nevertheless, if you’re reading this in 2020 and the Australian economy is in the toilet, remember: I tipped this.