For many of us, insurance seems like an integral part of financial life – something that you just buy when you’re a grown-up. But it turns out that insurance to protect individual people – “personal lines insurance”, as it’s known in the industry – has some interesting problems to overcome.

Insurance is a sales industry

The first problem is cost – notably, the cost of ‘distribution’.

Many people won’t buy certain types of insurance without prompting. Potential life insurance customers, for instance, are often unenthusiastic about contemplating their own demise or disablement.

The way the life insurance industry puts this is that life insurance is ‘sold, not bought’.

So the industry has always relied on a distribution network to do that selling – usually not employees, but insurance brokers and other types of agents.

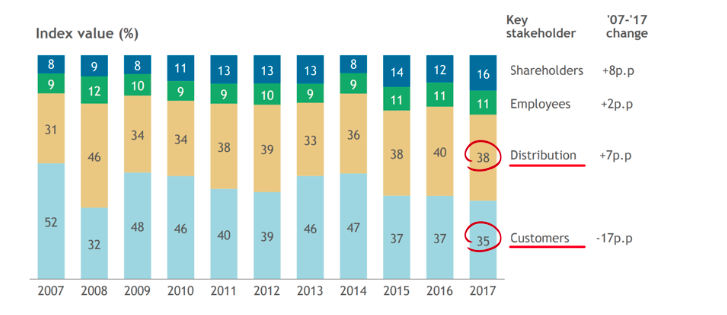

Those people cost money. Combine that with the ballooning demands of shareholders, and customers may now get less of the insurer’s total returns than the sales force does. One of the industry’s own think tanks, the Geneva Association, says distribution and administrative costs of 30% dent the economic appeal of insurance.

What customers actually get is best set out in a study released this year by Boston Consulting Group and Morgan Stanley, which published figures for Germany’s traditional life insurance business. If they’re right, and if Germany is typical, then life insurance customers now receive, on average, as little as 35% of the funds that this part of the industry generates.

Yes, barely a third.

Figure 1: Who gets insurers’ returns?

Here’s the proposition in the language of investment returns. “Life insurance: Put $1 in, get 35 cents back when you’re dead.”

If this doesn’t sound compelling, you may want to talk to a financial adviser. One caution: don’t talk to the adviser who’s getting commissions on your current life insurance policy.

Derisking life

A second problem is that insurers of all sorts sell protection against catastrophe. So they thrive best in an obviously insecure world. If much of the public feels it can cover its own losses, insurance faces a tougher time.

We often talk about the world the way Game of Thrones characters would talk about the night: dark, and full of terrors. The truth these days in an advanced Western nation can be rather different.

Many people’s lives are ‘derisking’. And as our lives becomes less prone to catastrophe, and the average age of the population rises, certain personal insurance products grow less necessary.

You may have superannuation (particularly in Australia, with its superannuation system) or a tax-protected savings vehicle such as the 401(k) in the US. You may have a home that has risen in value over a decade or more. If you have both, your life is increasingly sheltered from catastrophe. Many of today’s homeowners can draw on the equity in their home to cover unexpected expenses – a source of funds that has only really appeared in the past quarter-century.

Technology is helping to derisk society too. More houses than ever have smoke alarms that reduce the number of burn-downs. Cars come with electronic systems that protect against theft, and increasingly prevent collisions as well.

Self-driving cars will eventually make the roads even safer. In 2017, McKinsey estimated that car insurance premiums in the US “could decline by as much as 25% by 2035 due to the proliferation of safety systems and semi- and fully autonomous vehicles”.

For many home owners with adult children and no business that needs to be kept going after their death, life insurance is a less than compelling proposition.

Insurers have always joked that they sell a product that most consumers don’t really want. Their biggest problem may be products that people don’t need.

Trustworth practice

Personal lines insurance has one more problem: it seems to be an epicentre of untrustworthy practices.

Last week ASIC, Australia’s major financial regulator, released a review of the sale of consumer credit insurance (CCI), the stuff you may be urged to take when you take out a credit card or home loan. With CCI, the insurer will pay your loan repayments if unemployment, sickness or injury stops you from being able to do so.

ASIC’s published reports are often pretty tough; they would have told you about most of the bad practices in the banking industry long before the Hayne royal commission. But this report was tougher than most. The title gives away the ending: “Consumer credit insurance: Poor value products and harmful sales practices”.

For every dollar paid in CCI premiums, consumers got back just 19 cents. For credit cards, they got back just 11 cents.

Among other things, CCI has been sold to consumers who weren’t eligible to claim on insurance at all – for instance, because they were in some form of temporary or casual employment.

The behaviour is bad enough and apparently systemic enough for ASIC to name as one of its seven strategic priorities “addressing harms in insurance”.

For an industry that needs consumers’ trust, this is an obvious warning.