Most of us know the electric car’s save-the-planet proposition: the typical petrol- or diesel-burning car engine produces carbon dioxide and other climate-unfriendly greenhouse gases. We can lower emissions by replacing that engine with an electric motor powered by a battery.

But it turns out that the story doesn’t end there.

The lifecycle question

Yes, vehicles use energy for movement. But they also use another sort of energy – the energy it takes to build them. By almost all accounts, building an electric car consumes more energy than building one with an internal combustion engine. One reason: batteries themselves take a lot of energy to build, quite separate from the fact that they require charging once you buy them.

After it’s built, a battery-powered car creates fewer emissions than that a petrol- or diesel-driven car – but at that point it’s already behind in the emissions race.

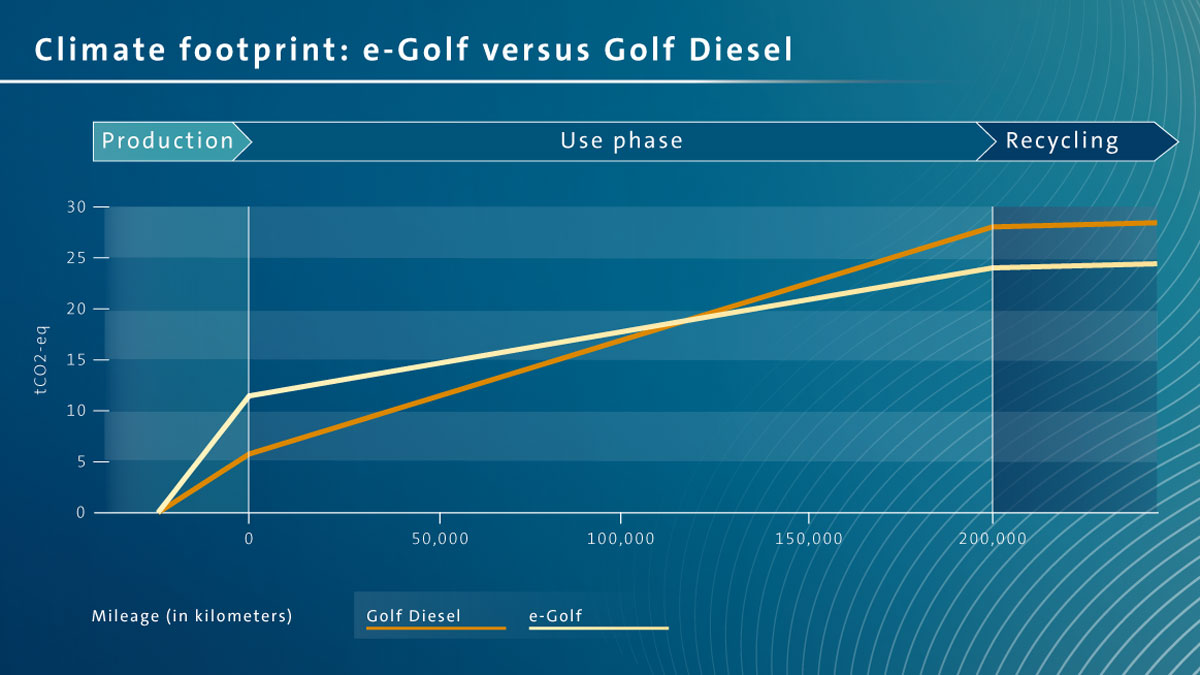

The question is: at what point do the emission cuts from using electric vehicles exceed the emissions increases from making them in the first place? Ideally, we want a graph showing the emissions created in a car’s manufacture, and then the emissions created with every kilometre that it drives.

I remember asking a federal government staffer for this graph three decades ago, but no such graph existed at the time. Now we have graphs that seem, well, reliable-ish.

The answer

Here’s one version of that graph, using VW’s electric and diesel Golf to represent electric and internal-combustion cars:

You can see that only after about 120,000 kilometres of driving does the electric Golf overtake in the low-emissions race. Before then, the internal combustion engine is ahead.

The asterisks

Now, a bunch of asterisks need to be added to this graph.

Firstly, this graph comes from Volkswagen – yes, that wonderful company that brought you the dieselgate scandal. That wonderful company that helped depress the reputation of the whole private business sector by lying through its teeth about its cars’ emissions. That Volkswagen.

So you’ve been warned. But VW, scarred by the experience, has been trying to clean up its act. So, for the moment, let’s not mention the dieselgate war.

The next asterisk is that emissions depend on how you generate your electricity. If you really want to sell a low-emissions vehicle, you’ll sell one that was built with solar- or wind-generated electricity.

Here’s another asterisk: that car will still have emissions. Currently, you can’t make a car without steel, aluminium, plastics, electronics and glass, and all of those will usually embody some emissions too.

If you want to sell an even lower-emissions vehicle, you’ll put in place some sort of offsets program to balance those emissions – for instance, by planting new trees.

A fourth asterisk is your recharging source. If you want to sell a vehicle with almost no emissions at all, you need to arrange for it to be recharged using electricity from clean sources too.

As it happens, Volkswagen says that it will be doing all of these things (although VW-branded green power will only be available in parts of Europe).

The future

For all the lies in its recent past, VW is now at least asking honest-sounding questions and giving honest-looking answers. Other studies come up with similar results to the graph above.

As much as I’d like to keep making snipes about VW’s past crimes, it looks like buying an electric Volkswagen really could be a climate-friendly purchase.

It won’t be wallet-friendly, though. Eventually, built at volume, electric cars should cost less than their internal-combustion-engine rivals, since they’re inherently less complex.

But in 2020, most electric cars are not yet being built in high volumes. So, the ID.3, VW‘s cheaper-to-make e-Golf replacement, is tipped to cost at least $45,000 in Australia and maybe $34,000 in the US. You can buy a similar-sized Hyundai for barely half that price.

Truly low-emissions-vehicles are coming only slowly, and they depend on efforts to de-carbonise global power grids – more than we might have thought.

Read next: Why electric cars are just the second-best solution